What’s digital radio all about?

First of all, what digital radio isn’t, is the “sit at a computer and type” mode that some, ill-informed, people have called it. It’s proper radio, with RF which follows the same laws of physics as any other mode. It has aerials which, if you don’t install them correctly, still don’t work – just like with FM. It has mobile and handheld radios (which are almost all dual-mode so they can be programmed with normal FM channels as well). It also has repeaters which can be networked together to increase their coverage area. Next, we are talking about a telephony mode – that is, you talk to people. With a microphone. So, it’s definitely not a data mode and there’s no typing! If you want that, go elsewhere. Lastly, it’s not elitist (or similar) – no more so than someone you know using a band you don’t have (yet). Some people want to use it and some don’t. If you want to join in, sort yourself out with some gear, you’ll be very welcome.

So, to continue….

As pressure on radio spectrum increases, the professional communications world is coming up with ways of squeezing more into less. That is more conversations in less spectrum. Inevitably, this technology is finding its way into the amateur world, often helped along by those same professionals.

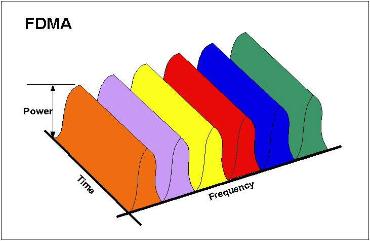

There are two fundamental ways of achieving this improved efficiency and every technique really boils down to one of these solutions. The first is to make each channel narrower – in the past we went from 25kHz channels to 12.5kHz and now there’s pressure for 6.25kHz channels. This is the method the likes of Yaesu’s fusion uses – in Fusion’s “voice and data” mode, a voice channel is fitted into 6.25kHz along with a data channel in a further 6.25kHz – still a total of 12.5kHz. In Fusion’s “voice only” mode, the single voice channel offered is still the same 12.5kHz wide that traditional analogue modes use. This is called FDMA or “frequency division multiple access”. FDMA is the spectrum allocation method radio amateurs are most familiar with – a given band is divided into fixed bandwidth channels (for example the FM portion of 2m or 70cm). “Going digital” using this method doesn’t offer us very much. We’d still get one digital channel on a given RF channel and we already have the ability to connect to other repeaters around the world – on the Isle of Man, our existing AllStar FM network is hard to beat in that respect.

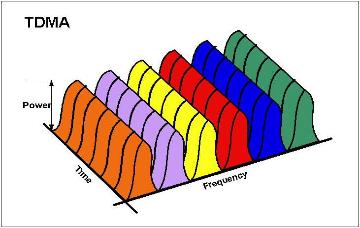

The second answer is to squeeze more conversations into the same space. This is called TDMA or “time division multiple access” and is the approach TETRA and DMR both take. In the case of DMR, the system rapidly switches between two channels on the same frequency. The total spectrum bandwidth needed is still 12.5kHz but now there are now two speech channels in the same space instead of one. This is where the term “timeslot” first appears when talking about digital radio – the first time period is “timeslot 1” and the second is “timeslot 2”. The picture below shows six timeslots but, theoretically, there can be any number. Remember, DMR is two – this means that can be twice as many DMR conversations fitted into a given band when compared with traditional analogue systems.

Finally, all digital systems offer potential advantages is improved coverage – some are better at it than others. This should not be confused with “bigger coverage area” though - it's still RF and it follows the same laws of physics of any other radio system - for a start, it still gets blocked by big bits of rock. By the nature of digital encoding and modulation, signals are very much either there or not – think of DAB and digital television broadcast systems. What that means in practical terms is that, firstly, there’s no mobile flutter and secondly, for areas where FM is noisy, digital systems will deliver clear speech. Experience has shown that DMR will work flawlessly down to a signal strength of around -120dBm, which is a horrible ropy and noisy, S1 signal in an FM system.

Why DMR and not Fusion?

The obvious question that comes up after reading the glossy adverts in the amateur radio magazines is “why doesn’t everyone use Fusion?” – after all, Yaesu are virtually giving the repeaters away. Apart from the fact that we wanted to keep what we had and add to it, rather than swapping it for something else, here are some thoughts…

The first answer is that their system is entirely proprietary – you can only use Yaesu radios with a Yaesu repeater. Even if you think Yaesu will still be making Fusion gear in five or ten years time, that’s only OK if you like Yaesu radios and they make one that suits you – there’s not much choice of gear.

The second answer is that DMR is an open standard – the opposite of things like Fusion. This means that there are several manufacturers that make equipment that inter-operates. That’s the way we’ve always worked – imagine having different types of FM so that only people with Icom radios could talk to other Icom owners but people with Kenwood gear couldn’t join in. There is one thing to say regarding the open-ness of DMR and that is that it is only the core that is open – there are various things that don’t work between manufacturers. This is limited to the likes of text messaging and security which are hardly a problem for amateur radio. Whatever, as a user, you still get the biggest choice of equipment with a DMR system.

The third answer is that DMR is a TDMA system, so we get two channels for the price of one. Extra for free is always good! That means that, depending on who’s doing what, we can potentially get two QSO’s on a repeater at once.

The fourth answer is that Fusion is an amateur system – that’s good on the one hand because it’s designed to be easy to set up but it’s all based on amateur grade hardware which is not designed to sit on commercial radio hilltop sites, running for ever, with little attention.

Do you want another reason? The fifth answer is that it’s the way the world is going. Whether we like it or not, analogue systems are slowly being phased out in the commercial world and, at the moment, DMR seems to be the most rapidly growing system there. That means the supply of equipment suitable for us to use is unlikely to dry up. There’s gear on eBay and plenty of choice of suppliers of new equipment. As well as the established suppliers such as Motorola, the Chinese are beginning to enter the market with less expensive handheld radios and most PMR radio equipment manufacturers are making DMR equipment as well as their traditional analogue systems.

What we are doing.

We’ve decided to go digital with DMR for all the reasons already mentioned above.

This is being achieved with the installation of two Motorola repeaters, co-sited and sharing antennas with the existing 70cm FM repeaters at Carnane and Bride. This is being done without adversely affecting the FM repeaters.

Amateur DMR repeaters are generally inter-connected but it should be mentioned that there are two, separate DMR networks. The first is DMR-MARC and the second is DMR+. The difference is really down to the hardware used by the repeater network (as distinct to the radios individuals use to access the network). DMR-MARC is Motorola based and DMR+ is Hytera based. DMR-MARC originated in America with the Motorola Amateur Radio Club and is, by far, the biggest network in the UK. DMR+ originated in mainland Europe and is the biggest network in Holland and Germany and although our close neighbour, GB7FC in Blackpool is part of the DMR+ network, it is very much the minority network in the UK.

At the moment, the two networks are not connected to each other meaning that repeater keepers have to choose. There are, however, some interesting software developments currently underway which might mean that’ll change some time in the future.

We’ve decided that our repeaters will soon be connected to the DMR-MARC network since this includes most of the existing UK DMR repeaters.

Talkgroups, timeslots and colour-codes…

Talkgroups, timeslots and colour-codes are the buzz-words that are used to describe the bits of information used to define the operation of a DMR radio system. Everyone who uses a DMR radio in the amateur radio world needs to know what they mean to avoid too many mistakes….

Timeslots have already been mentioned – they simply describe the time periods used for the two channels we can access. The first one is “timeslot 1” and the second is “timeslot 2”. It doesn’t matter why 1 is 1 and 2 is 2, just so long as every radio in the system has the same idea.

Colour codes are a bit like CTCSS tones in FM systems and are used to distinguish between repeaters on the same frequency. In the FM system on the Isle of Man, Carnane uses a CTCSS tone of 110.9Hz and Bride uses 71.9Hz even though they are both on a frequency of 430.8250MHz. The DMR system uses a colour-code of “2” for Carnane and “3” for Bride. For a user, it’s just a number you need to know when you programme a DMR radio.

Talkgroups are an extra thing we get in DMR systems. It’s a phrase that comes from commercial trunked radio systems and they are a way of distinguishing between groups of users. It can be thought of by comparing our DMR system with the government’s TETRA system where one talkgroup could be used by the Snaefell trams and another by the bus drivers. Each channel programmed into an amateur DMR radio is configured to only un-mute when signals directed to its talkgroup are received.

There’s more on talkgroups and timeslots as applied to the DMR-MARC network later…

DMR ID number

Every radio in a DMR system has an ID number, whether it’s a repeater or a user’s radio. This is a bit like a callsign which is embedded in the transmitted signal. Every transmission includes the ID number for that radio – this is normally used in the amateur radio world to display the callsign and name of a transmitting station on a user’s radio.

In the amateur world, ID numbers are generally allocated, one at a time to individuals and repeaters. The exception to this is for shared radios – in that case each radio has an ID. Generally though, the rule is that an individual number is allocated to each piece of equipment that could conceivably appear on the network at the same time. So, if you have a handheld and a mobile that only you use, you’d have one number applied to both but if you loan your handheld to other people, you’d apply for a second ID number.

The ID numbers are organised on a regional basis – for example, a number beginning with 235 is allocated to the UK (and islands) – like a “G…” callsign. From that set of numbers, anything beginning with 2356 is allocated to the Isle of Man, like a “GD… “ callsign.

Channel zones

All the manufacturers of DMR radios we've looked at follow this method of defining channels when they are programmed. In the case of Motorola, it is rigidly upheld but in the case of Hytera, it is less so.

A channel zone is simply a group of channels – usually this is a group of sixteen channels. Normally, radios are programmed so that if the user starts scanning, then only the channels within the selected zone are scanned. That means a repeater can be monitored for activity on any of its configured talkgroups.

Generally, when programming a radio, a channel zone is used to group all of the channels defined for a particular repeater. So, there is a zone for each repeater and, within each zone, a set of channels which are all for the same repeater but use different combinations of talkgroups and timeslots.

Hytera radios can be programmed such that their channel selectors will scroll either through all the available channels or just those in the current zone. Motorola radios are restricted to just the currently selected zone. In both cases, the zone is changed either from a menu or a button, depending on how they are programmed.

Of course, you can do what you like to organize the channels when you programme your own radio...

More talkgtoups, timeslots and operating on our repeaters

A condition imposed by the DMR-MARC network on repeaters wishing to join is that they operate on a number of talkgroup and timeslot combinations. This is done to maintain standard operation for users across the network.

The channels (meaning a combination of talkgroup and timeslot) on the Isle of Man repeaters are shown here…

|

Timeslot |

Talkgroup |

Usage |

|

1 |

1 |

Worldwide calling |

|

1 |

2 |

Europe |

|

2 |

8 |

Regional group |

|

1 and 2 |

9 |

Isle of Man (both CA and BR) |

|

1 |

13 |

English speaking world wide |

|

1 |

113 |

World wide English, user activated 1 |

|

1 |

119 |

Worldwide, user activated 1 |

|

1 |

123 |

Worldwide English, user activated 2 |

|

1 |

129 |

Worldwide, user activated 2 |

|

1 |

235 |

UK wide |

|

1 |

2353 |

GB7PN link |

|

2 |

9990 |

Echo back audio test |

It should be apparent that there are some differences between DMR and analogue repeaters – quite aside from the technology used to implement them. Anyone making use of DMR repeaters needs to bear in mind some straightforward ideas based around their choice of talkgroups and timeslots.

First thing to bear in mind is that when you operate on a DMR repeater, you are, potentially accessing other repeaters at the same time. The network does that on its own and is the way it’s meant to work. For example, using talkgroup 1 (the world wide calling group) will access every repeater in the DMR-MARC network. That might be what a user wants but they should remember to keep their conversation short. So, the rule there is “pick the talkgroup that covers the smallest area you need to complete your conversation”. If you want to speak to someone on the island, use the “Isle of Man” talkgroup. If you want to speak to someone in Liverpool, then the “regional” talkgroup is the one. Of course, there’s always the option to use one of the simplex channels…

In order to minimise traffic on the worldwide talkgroups, "user activated" talkgroups have been implemented on the MARC network. These are talkgroups 113 and 123 for English speaking places or 119 and 129 for the rest of the world. Repeaters carrying these talkgroups (like ours) will only connect to them following some local traffic. The repeater will remain connected until there has been five minutes of no local activity. So, best practice when making long-distance calls is to first call CQ on talkgroup 1 or 13 and then change to either talkgroup 113 or 123 to complete the contact.

Second thing is, there is a “regional” talkgroup – that is the north-west of England and us. We decided that this was what we wanted since most off-island repeater talk at the moment is with people in the north-west.

Thirdly, there is an “Isle of Man” talkgroup. This sounds obvious until you realise that, in the rest of the network, locals use the “local” talkgroup on their repeaters. In the DMR-MARC world, this is defined as “this repeater” which makes a repeater appear to the user as a traditional stand-alone analogue one. In the Isle of Man, it’s more likely that our local users will expect to access all the island’s repeaters at once like they currently do with the FM system. We didn’t want to define our “regional” talkgroup as just the island, so we have asked for another one – the “Isle of Man” talkgroup and,so, our talkgroup 9 links both repeaters.

Finally, there are "direct-dial" talkgroups. Each repeater in the UK (and us) has one of these allocated. The Isle of Man direct-dial talkgroup is 934. When a call is initiated on timeslot 1 on a repeater, using one of these talkgroups, a temporary link is made between the two. This lasts until five minutes of inactivity occurs. The call will appear on the destination repeater on talkgroup 9, timeslot 1. So, to make a call back to the island from another UK repeater, use timeslot 1 and talkgroup 934. This will appear on both CA and BR, talkgroup 9, timeslot 1. A full list of direct-dial talkgroups is on the UK C-Bridge website http://www.cc-3.net.

With the wide variety of talkgroups and timeslots available, it is worth mentioning the good practice of announcing which you are using when you make an initial call through the repeater. This makes it easier for someone to come back to you if they leave their radio scanning for activity.

What do you need to join in?

The answer to that is the same as any mode or band you want to use, a radio and antenna. You have the same choice as you do with traditional FM, between handhelds and mobiles. The aerial you pick depends on all the same things as it does for FM and the aerials are exactly the same – remember it’s “proper” radio and there's no such thing as a "digital aerial"…

There are several manufacturers to choose from, the easiest to get hold of and programme being Motorola or Hytera for professional grade equipment and either Connect Systems or TYT for amateur grade gear. Remember though, you get what you pay for in terms of quality. Other professional manufacturers such as Tait, Vertex and Kenwood also make DMR equipment but, for amateurs, the programming software is often more difficult to obtain.

Generally speaking, the various “high-end” radios are the most suitable for amateur use since they offer plenty of channels, an alpha-numeric display and a contact list. The alpha-numeric display is useful to help keep track of what’s programmed into the channels – a typical high-end radio will be capable of around 1000 channels so relying only on channel numbers soon becomes difficult. The contact list is useful to allow the radio to display a callsign and name instead of just an ID number when somebody calls. Most manufacturers offer variants of equipment fitted with GPS – this is not applicable for the DMR-MARC network, so you can save a few pounds by buying the non-GPS version. Having said that, if a radio has GPS fitted, it will still work fine – just don’t enable the GPS beacons.

For Hytera radios, a keypad is useful as it enables frequencies etc to be entered in the field-programming menu. This allows changes to be made to the channel programming without using a PC. For Hytera mobiles, a keypad is only available on the DTMF microphone – so buy one of those if you want to use the field-programming menu.

For Motorola radios, the field-programming menu offered is not really of any use for amateur radio. However, generally, there’s a keypad anyway on radios with enough channels for amateur use.

One other important thing to note is that if you buy a handheld radio and want to connect an external antenna to it then take care that yours is one of those that has a traditional RF connector on it. For example, the Hytera PD785 has an SMA connector but the Motorola DP4801 uses a threaded metal ring so it is not possible to use it with any other aerial.

The following pictures show some of the popular and readily available equipment.

TYT MD-380

Motorola and Hytera handhelds

Motorola DM4600

Hytera MD785

The choice of equipment is very subjective but recommended high-end radios are currently (September 2015):-

- Hytera MD785 or Motorola DM4600 mobiles

- Hytera PD785 or Motorola DP4800 handhelds

Lower cost options are the TYT MD-380 or Connect Systems CS-750. Others to consider are the Motorola SL1600 which has 99 channels in two zones or the Hytera PD365 which has 128 channels in 16 zones. Both of those handhelds are smaller than the high-end radios and the SL1600 has a clever display that is (almost) indestructible. There is also a Hytera mobile, the MD655, which has its display and speaker on the microphone. The display on this is quite limited making it less useful for amateur use unless only a few channels are programmed. All of the above radios can be programmed with standard FM as well as the new DMR channels.

Since DMR is a relatively new technology, there is less second-hand equipment around but eBay is the place to look. Typical equipment to be found there include Motorola’s DP3600 mobile and the DM3600 mobile, which are the forerunners to the current DM4600 and DP4800 radios. If you're getting a handheld, make sure you get a charger too - usually commercial radios use drop-in chargers. Make sure whatever you find is UHF and don’t buy anything that mentions dPMR or doesn’t say anything about MotoTRBO or TDMA because they are something different. Also bear in mind that batteries in handheld radios don’t last forever, particularly in commercial use. Replacements aren’t cheap andthings can become complicated if you try and buy anything other than genuine ones.

Whichever route you take, you’ll probably want to be able to programme the radio yourself. Even if you buy something ready-to-go from one of the dealers, you’ll probably want to change how the buttons work or add channels sooner or later. For that you’ll need the programming software, or CPS (customer programming software), as well as a programming lead to connect it to your computer.

If you have a Motorola radio, the only legitimate way to get the software is to buy it, along with the lead, from a Motorola dealer – that’s quite expensive with the software currently being around £100. Some of their radios (SL1600) use standard USB leads but others (DP4800, DP3600) use special cables which are generally in the £50-60 region on eBay. Of course, you can find pirated copies of the software on the Internet if you are prepared to take the usual computer virus risks….

Hytera has a different business model and they provide the software to their dealers for free, leaving it to them how they distribute it. As a result, their software is freely available through the Dutch amateur community that runs the DMR+ network. The cables are available from the same dealers who sell the radios.

The software for the various Chinese radios is generally free and the leads are either included with the radio when you buy it or cheaply available on eBay.

The last thing you need is a codeplug – that’s a Motorola term for the configuration file generated by the programming software. It applies whatever radio manufacturer you pick. You can either make up your own or use someone else’s. If you use someone else’s, then you need to make sure you change the DMR ID number. Several dealers provide radios already programmed, in those cases, you let them know what your ID number is when you buy the radio.

A useful website for non-Motorola programming software is http://ham-dmr.nl – it’s all in Dutch but Google Translate works very well and, most users will soon learn that “Bestanden” is Dutch for “Downloads”. The Hytera CPS and firmware updates are currently available there along with the CPS for both Connect Systems and TYT radios.